This is the window that adorns Greenford Methodist Church. It depicts Christ in Glory flanked by St Mark on the left and St Peter on the right, each with their symbol in a shield - a lion for Mark and keys for Peter. Christ has his right hand raised in blessing while, above his head the Holy Spirit descends as a dove. The alpha and omega symbols show Christ as the beginning and the end. The dedication at the feet of Christ show the window was given in memory of Alfred and Edith Preedy.

The depiction of Christ in Glory flanked by saints is pretty conventional and I’m sure art critics would say that there is nothing particularly exceptional about the window. However, with its vibrant colours I always find the window striking and my eyes are constantly drawn to it, taking in its various details. Many churches have stained glass windows but only occasionally do I come across one that I find arresting. This is one of them.

The depiction of Christ in Glory flanked by saints is pretty conventional and I’m sure art critics would say that there is nothing particularly exceptional about the window. However, with its vibrant colours I always find the window striking and my eyes are constantly drawn to it, taking in its various details. Many churches have stained glass windows but only occasionally do I come across one that I find arresting. This is one of them.

Light has had a great and deep symbolism for Christian thinkers down the centuries. In mediaeval theology, God concealed himself so as to be revealed and light was the principal and best means by which humans could know him. The theology of Dionysius the Aeropagite, a 1st century Greek convert to Christianity and an Athenian judge at the Aeropagus Court was based on one central idea: God is light. As Robert A.Scott in his book The Gothic Enterprise writes of the Aeropagite’s thinking, “Every living creature, every material object that is visible stems from this initial, uncreated, creative light. All living creatures and all material things receive and transmit the divine illumination from which they emanate. ….. In this view, the universe, born of irradiance, is tantamount to a descending flood of light that touches everything and unites it, giving order and coherence to the entire world.”

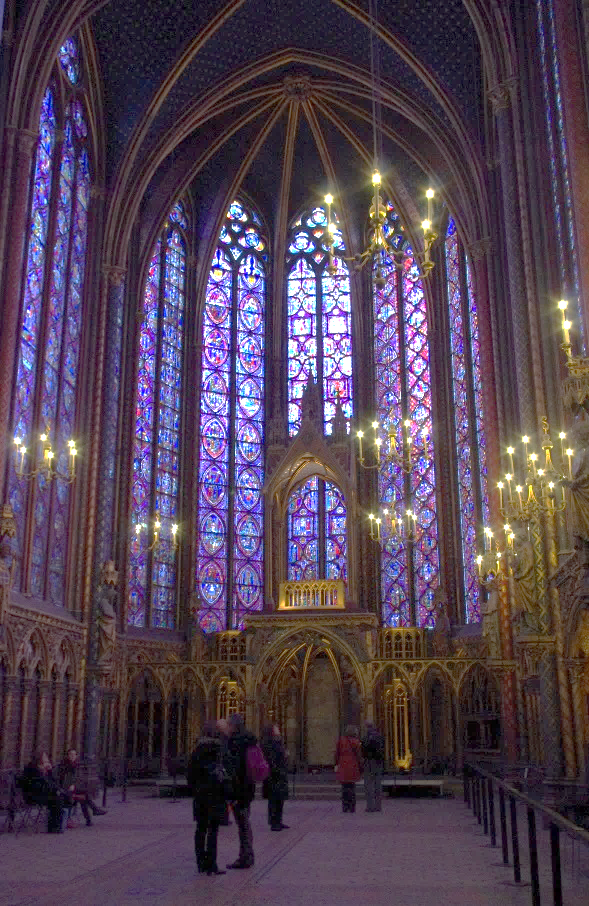

In 1144 a newly completed choir was dedicated at the abbey church of St Denis in Paris. This new choir, the brainchild of Abbot Suger incorporated an architectural innovation that would, in many ways revolutionise church design – the pointed (or ‘Gothic’) arch. Up to then, major churches had been built with arcades of rounded arches and heavy thick walls to guarantee stability with only small windows. The pointed arch is structurally much stronger and permitted walls to become lighter and, importantly window openings to become bigger. The later development of the external ‘flying’ buttress allowed for yet lighter walls to the point where structures could become virtually frameworks for walls almost entirely composed of windows. A prime example of this is the upper church of La Sainte Chappelle in Paris (right) where the windows stretch from the vaulted ceiling almost to the floor.

In 1144 a newly completed choir was dedicated at the abbey church of St Denis in Paris. This new choir, the brainchild of Abbot Suger incorporated an architectural innovation that would, in many ways revolutionise church design – the pointed (or ‘Gothic’) arch. Up to then, major churches had been built with arcades of rounded arches and heavy thick walls to guarantee stability with only small windows. The pointed arch is structurally much stronger and permitted walls to become lighter and, importantly window openings to become bigger. The later development of the external ‘flying’ buttress allowed for yet lighter walls to the point where structures could become virtually frameworks for walls almost entirely composed of windows. A prime example of this is the upper church of La Sainte Chappelle in Paris (right) where the windows stretch from the vaulted ceiling almost to the floor.

Combined with other elements of Gothic design such as the construction of buildings in line with ideas of structural harmony and geometrical proportion, these developments allowed the builders of our great churches to incorporate light into their designs to realise their vision of church buildings as images of the heavenly New Jerusalem. Robert A.Scott again, “As the worshippers’ eyes rose toward heaven, God’s grace, in the form of sunlight, was imagined to stream down in benediction, encouraging exaltation.”

All this might lead you to imagine that mediaeval cathedrals and great churches were light, airy places. In fact, where mediaeval glass has survived intact, to modern eyes great churches often seem dark and gloomy. A good example of this effect can be seen at Chartres cathedral in northern France which retains almost all its mediaeval glass. Sunlight was not just allowed to flood into buildings, it was used to illuminate coloured glass depicting not only images, scenes and stories from the Bible but also aspects of daily life and the trades of the donors of the windows.

Sadly, much mediaeval glass in English churches was destroyed during the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. Some fine examples do, however survive such as the great east window in York Minister and in parts of Canterbury Cathedral. There are also other fine examples notably at Malvern Priory in Great Malvern and in St Mary’s church in Fairford, Gloucestershire which has the only complete set of late mediaeval glass in England.

The Protestant reformers laid great emphasis on the (spoken and written) Word of God and saw images as being idolatrous. However, to the illiterate, images could have a didactic use telling stories from the Scriptures in pictures, for example these roundels from Canterbury Cathedral showing the Marriage at Cana (left) and the Three Kings being told by the angel in a dream to return home without going back to Herod first.

Modern glass can be striking and intriguing.  This example from the Art Deco period is in the Franciscan church in Krakow and seemingly shows Christ, or perhaps St Francis, in torment. I’m not sure. Either way, the window invites you to stop and to contemplate.

This example from the Art Deco period is in the Franciscan church in Krakow and seemingly shows Christ, or perhaps St Francis, in torment. I’m not sure. Either way, the window invites you to stop and to contemplate.

Whether mediaeval or modern, all these windows have the medium of light in common. We may no longer think of light as a great unifying principle as did the mediaeval theologians, but light is still hugely symbolic. As John 1:4-5 has it, “In him was life; and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness but the darkness has not understood it”.

So, next time you sit and look up at the window in Greenford, contemplate it for a while and let its message of Christ as light and as Saviour seep through.

Photos by Gerald Barton

Quotations from Robert A.Scott “The Gothic Enterprise; A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Cathedral”, University of California Press, 20